“Actions prove who someone is; words just prove who they want to be.”

Recently, I made a change in my behavior and got serious about my waste stream. There wasn’t any one thing which spurred me to alter my daily routine, but it evolved out of a need for concrete action in the wake of the reverse gear in which we are stuck at the moment and the eponymous victimization that’s taken hold of our society in a dance complete with fury and sanctimony.

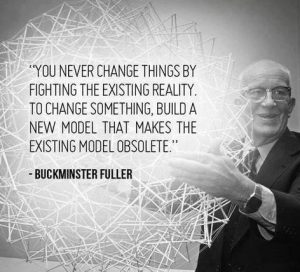

Somehow, taking a small step to change my behavior in the current environment seemed like a radical act, even though I didn’t proclaim the change publicly (until now), nor have I tried to convince anyone else they should follow my lead. I simply wanted to test the hypothesis that each of us can be the pebble that starts the ripple in the pond.

For the last couple of months, every vegetable peel, apple core, moldy piece of bread, salmon skin and anything in the kitchen that doesn’t end up in my mouth goes into a lovely Bed, Bath and Beyond stainless steel container, lined with a biodegradable bag that gets taken out to the composting dump every three to four days.

Now, I’ve been a conscientious recycler for a long time and bring my reusable bags with me to the grocery store, but by removing the food waste, I’ve reduced the number of times I have to take out the trash from once every five or six days to once every nine or ten days. If we didn’t have a cat, it would probably be even less frequent, but cat odors fall into their category of Darwinian mutations.

Cat-tasrophe!

Unfortunately, the ripple of change I’m creating extends only a couple of concentric circles before it reaches an artificial barrier that shuts down the momentum. That barrier has a name which encases our society, and it’s called plastic.

While I’ve now dealt with most of the methane gasses produced in my home (sans the cat), what remains is a different sort of evolutionary mistake. Petrochemically-based plastics are made up of three elements: oil, water and energy. We’ve produced more of it in the last decade than in the entire last century, and one-third of the 300 million metric tons produced each year is still unrecyclable. We are the plastic generation, and you need to look no further than your garbage to prove it.

At least 70 percent of what remains in my trash after recycling and composting is plastic food wrapping, plastic package wrapping, plastic bottle caps; the list goes on and on.

Drowning in plastic isn’t new news to many of you, especially those of you who’ve been composting for years; however, the problem remains. And among those who pay close attention to such matters, the answers are roughly divided equally between the unlikely and the implausible. Why? Because those are backward looking solutions.

Ever since the invention of the wheel, humanity has loathed voluntarily giving up its comfort, and plastic is nothing if not about convenience. Our food producers use plastic because it’s cheap and it moves the process along quickly, things consumers demand. The same goes for toy makers, car makers, makers of hospital equipment like IV bags, and ironically, garbage bag producers.

Arguments to reduce plastics generally fall into one of two camps: don’t buy any of these things made with non-recyclable plastic, or use a less convenient alternative–and both tactics are designed to fail.

It’s been 15 years since I had to change a diaper, but the memory is still vivid enough (especially with boys) that I’m not going to cast the first stone at exhausted parents who opt for speed and sleep. And lest you find me too smug, I also still use plastic garbage bags to line my garbage can.

Conservation is an important message too often lost in our society as we move faster and faster, but even if adequately incentivized, it won’t be the solution that unclogs our landfills and oceans because it’s fundamentally at odds with a consumer-based society.

We need to look forward, and that’s where cleantech can change the paradigm because it’s not chaffing against the engine of progress.

Bioplastics

Bioplastics, which are derived from biological substances instead of petroleum, and are biodegradable are slowly making their way into consumer products. Thanks in part to European bans on plastic bags and straws, the bioplastics market is worth $1.1 billion today and is forecast to rise to a $1.7 billion market by 2023.

In America, Kraft is putting resources behind efforts to make its food packaging more recyclable, reusable or compostable, while a consortium called NatureWorks has launched a bio-based drinking straw and DuPont and Archer Daniels Midland have partnered up to make plastics out of fructose. These multi-billion dollar corporations can read the writing on the wall: consumers have looked at their waste streams and are demanding a more sustainable alternative–and there’s money to be made.

Several years ago, the U.S. government made it even easier for consumers to choose bio-based products through the BioPreferred program. You can visit the USDA website for the catalog of products, or you can look for the USDA Certified Biobased labeling on products, earned through testing at independent third-party laboratories to ensure integrity.

Look for the BioPreferred Label.

Does this spell the end of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch? Of course not. But in an age when the extent of action is considered a firebomb on your Facebook feed, these pebbles are at least expanding our horizons outward.