I recall watching the Brexit election and thinking this was all a figment of dog-whistle nativism. It’s not like the tropes the Brexit Yes side was trotting out were anything we hadn’t heard in the U.S.: “Immigrants and globalism are destroying our native hegemony and culture.” “We aren’t going to be subjugated to a bunch of pointy heads working for the EU in Brussels who think they know what’s best for England!” If I was a British citizen, I would have voted no on Brexit because history is replete with the wealthy concocting schemes and strawmen to convince poor people that immigrants are responsible for their personal and financial difficulties. Besides, when your country’s capital is the global headquarters of international finance, it seems counterintuitive to want to shut out the rest of the world. Over the last couple of weeks, however, the acronym GDPR has given me a more nuanced understanding of why some Brits are so anti-Brussels.

GDPR stands for General Data Protection Regulation, and it’s the European Union’s attempt to protect people’s privacy online and ensure their data isn’t collected without their permission. At its surface, we should all stand up and applaud the EU as personal privacy is one of this era’s defining issues. The GDPR sets up a bureaucracy to police how your data is used–again if you care about your privacy this should be considered a win. If you live in an EU country, you can’t even make the argument that you don’t have representation because every EU state has a member of the oversight board. Game, set, match–as long as you live in Western Europe–but I don’t.

My clients and my contacts are in North America, but since the E.U. comprises hundreds of millions of internet users, all companies with a global reach have to adhere to these rules, which in turn means all North American internet users who interface with Amazon, eBay, Facebook, Google, Apple and the other global tech behemoths who have come to dominate our lives have to adhere to the GDPR as well with no voice in the matter.

But if this is all about protecting data privacy, why am I wasting an hour of my life writing about it? Two words: collateral damage.

One of the ways I help my B2B clients is by designing email programs for them to communicate within their company, their industry, the media that covers their industry and their customers. Sometimes they are selling something, but more often they are providing thought leadership or company news. Their contact lists include people and organizations with whom they have deep and longtime ties; however, under the GDPR that’s not a sufficient reason to add them to your email list.

If your company is using a commercial email platform, which is the norm in most small to medium size businesses, it is likely you will have to get affirmative consent from each of your subscribers in order to keep them on your email list. Why? According to some of the most knowledgeable attorneys on the matter:

Third-party processors and controllers who work with the personal data of EU citizens and residents may have additional GDPR obligations, regardless of physical location. And outsourcing to a third-party processor outside of the EU doesn’t absolve a company of its own GDPR obligations.

That means if you use Constant Contact or have even one European on your email list, you are going to have to grit your teeth and get explicit permission from every single one of your contacts in order to continue to communicate with them through a third-party service. How do you do this?

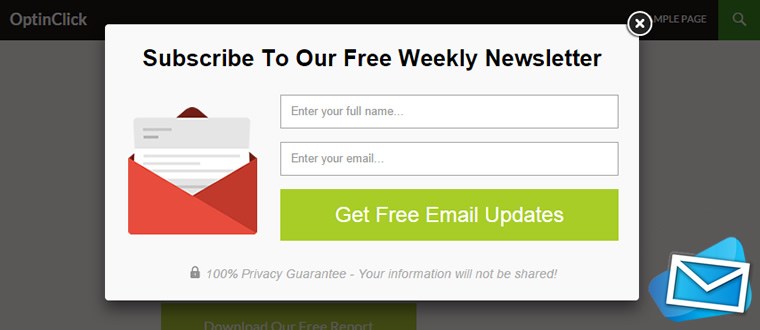

Switch from an opt-out to an opt-in approach in which everyone has to give you permission to send them something as innocuous as a newsletter. Consent may include checking a box on a website, choosing technical settings specifying the type of information the user wishes to receive or another statement that clearly indicates consent to the processing. Silence, pre-ticked boxes or inactivity in response to an inquiry is not adequate.

On my own personal listserve, I’ve begun the process of reconfirming each and every one of my 2,000 subscribers–and I curse Brussels with each and every request I send out and confirmation I get back. I realize this is being done for the greater good, but like all innocent parties since I can’t take my frustration out on the spammers and data thieves who’ve caused this breach of trust, I’m left with only one direction to point my shaking finger: those damn bureaucrats in Belguim messing with my life. Though it’s not their fault, this is how brushfires break out into Brexits.